Cognitive engagement is vital to keeping your brain healthy since it can slow shrinkage and induce neuroplasticity. While modern technology offers many new tools and games to keep your brain active, are they better than traditional puzzles like crosswords? Dr. Murali Doraiswamy of Duke University joins the podcast to talk about his recent study, in collaboration with principal investigator Dr. Dev Devanand of Columbia University, on the effects of daily crossword puzzles on the brain health of older adults in comparison to daily computerized games.

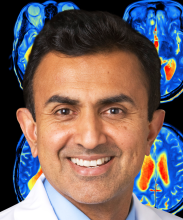

Guest: P. Murali Doraiswamy, MBBS, FRCP, director, Neurocognitive Disorders Program, physician scientist, Duke Institute for Brain Sciences, professor of psychiatry and medicine, Duke University School of Medicine, co-author, The Alzheimer’s Action Plan

Show Notes

Learn more about Dr. Doraiswamy on Duke University Department of Medicine’s website.

Read Drs. Devanand and Doraiswamy's study, “Computerized Games versus Crosswords Training in Mild Cognitive Impairment,” through the New England Journal of Medicine Evidence.

Connect with us

Find transcripts and more at our website.

Email Dementia Matters: dementiamatters@medicine.wisc.edu

Follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

Subscribe to the Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center’s e-newsletter.

Transcript

Intro: I’m Dr. Nathaniel Chin, and you’re listening to Dementia Matters, a podcast about Alzheimer's disease. Dementia Matters is a production of the Wisconsin Alzheimer's Disease Research Center. Our goal is to educate listeners on the latest news in Alzheimer's disease research and caregiver strategies. Thanks for joining us.

Dr. Nathaniel Chin: Welcome back to Dementia Matters. Today I'm joined by Dr. Murali Doraiswamy, professor of psychiatry and medicine at Duke University School of Medicine. He's also the director of the Neurocognitive Disorders Program, a physician scientist at the Duke Institute for Brain Sciences and a leading researcher in the field of cognitive fitness and brain health. He has been an advisor to leading government agencies, businesses and advocacy groups and is the co-author of the book, The Alzheimer's Action Plan. In October 2022, he published a study in the New England Journal of Medicine Evidence, which looked at how crossword puzzles impacted cognition for individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) compared to computerized cognitive games. Dr. Doraiswamy, welcome to Dementia Matters.

Dr. Murali Doraiswamy: Thank you for having me on the show. Before I start my interview I would like to acknowledge Dr. Dave Devanand, professor of psychiatry at Columbia University. He was the principal investigator at Columbia University, and this was a two-site study done between Columbia University and Duke.

Chin: I'm excited to have you here because I know your work is going to touch many important areas that our listeners and people in my clinic and in the research group are wanting to hear. To start, can you tell our listeners a bit about yourself and how you got involved in this area of research?

Doraiswamy: Sure, I’d be glad to. I think this is one of the most interesting and exciting areas of research within brain science. We all know that the brain is our biggest asset. We are in the fourth industrial revolution, which is really a cognitive revolution. The biggest threat to the fourth industrial revolution is the threat of dementia. Worldwide something like 40 million adults or 50 million adults have Alzheimer's disease and another 100 to 200 million people may be at increased risk for Alzheimer's. Despite 50 to 60 years of intense research spending 30 to 40 billion dollars we don't really have a good way – a definite way – to prevent Alzheimer's disease and that's what we need. We now know that something like 40 percent of the risk for Alzheimer's disease may be lifestyle related, which means that we have an opportunity to devise lifestyle interventions to reduce our risk. That's the reason why I got into this and that's the reason why I've dedicated the last maybe three decades of my life to finding a preventive strategy for Alzheimer's disease.

Chin: I've never heard of the fourth industrial revolution, but I must say I love that. I couldn't agree with you more, our cognition is so important to people. It's a part of our identity and I know our listeners and I both agree that we’re appreciative that people like you are in the field and pushing this forward in ways that are not necessarily medication-driven but other things that we all have access to.

Doraiswamy: Absolutely, there's an old saying that says, “Genetics loads the gun, lifestyle pulls the trigger.” A lot of our research is focused on finding the genetics and molecular pathological abnormalities. Only a small proportion of the worldwide research funding is dedicated to finding lifestyle related cures.

Chin: I'll say when I'm in my memory clinic that's what we talk about. This is what the desire is. It’s for this type of information: “What can I do now?” “What do I not need a prescription for?” “How can I help my brain?” I'm excited to talk about your study in particular, so let's just get to it. You randomized participants to either a group that engaged in computerized cognitive games or to computerized crossword puzzles for 78 weeks. Before you talk about your results, tell us, why did you choose crossword puzzles?

Doraiswamy: We've known for about three or four decades of a phenomenon called neuroplasticity, that is the older adult brain retains the capacity to change. We've also known from a number of observational studies that complex mental activities can reduce our risk for dementia. However, there is little consensus on what is the best type of complex mental activity. How long should one do it? What is the right dose? In the era of pandemics, we became acutely aware of the importance of remote care, of home-based care and computer-based delivery of interventions. The question we were really interested in is, “Can something that's sort of a hundred-year-old pastime, something simple – Crossword puzzles – how does this match up to a very sophisticated computerized suite of games that can cross-train different aspects of your brain?” That was the question that we sought out to address in our study, “Can a one hundred-year-old pastime beat a relatively young 20-year-old teenager played on the computer?” [Laughs]

Chin: [Laughs] That is a great question. I do have questions for you too about duration and dose and intensity, but we'll get to those in a few minutes. Beforehand, how are computerized crossword puzzles and computerized cognitive games different from your perspective?

Doraiswamy: Well, computerized cognitive games are interesting because some people like computers. Some people like the fact that you get instant answers. Some people like the fact that with computerized games you can specifically train very, very narrow domains of your cognitive functioning. For example, you can just train reaction time. You can just train your math ability. You can just train your spelling ability. You can just train executive functioning ability. The beauty of computerized games is it can scale its difficulty based on how well you did last time and you can get 100 different metrics from a computerized game. On the other hand, crossword puzzles is sort of very old-fashioned. It's almost like a complex mental activity that draws on multiple aspects of your brain but it doesn't hone in on any one specific ability. It's also not a timed game. Usually we sit on our porch with The New York Times and some people do it for two hours or three hours. Unless you go through like the Monday times, the Tuesday times, the Wednesday times, you can't really grade the complexity of the puzzle. You're sort of stuck with the puzzle that you have until you get the next day's paper, so there are very two different types of interventions. One is very easy for an older person to access. They're familiar. The other is the much more newer sort of way of doing things and it's easier to score. It's easier to automatically administer. It's easier to scale worldwide.

Chin: I appreciate those descriptions because I was able to visualize a person sitting on their porch with their cup of coffee with a pencil and entering in letters on the crossword puzzle and then this new age, someone at a computer doing something fast and clicking and having it be sort of a game versus anything else.

Doraiswamy: Exactly.

Chin: They're great comparisons. I think it's wonderful that you're able to do both.

Doraiswamy: Thank you. That was the goal of the study, the old versus the new.

Chin: I suppose a part of it is to maintain engagement, because if people are bored by something they're not going to continue to do it for 72 weeks. So you were successful in being able to keep people actively involved in this whole process.

Doraiswamy: 100 percent. The first thing we discovered even before we did this study – we did a scoping review of other digital therapeutics in the brain health space. The first thing we discovered was that engagement is crucial. Some 80 to 90 percent of computerized digital interventions there's very high engagement the first week, two weeks and then 80 to 90 percent of people drop out after the first two months, which is of no use. We really wanted high engagement in order for a treatment to have sustained effects because we know these are chronic conditions and you need chronic intervention.

Chin: In your study, the participants fit a certain criteria and they all had what's called mild cognitive impairment. I know our listeners who listen regularly know that or know what that categorization is, but can you share with us, why did you focus on this group? How did you define this particular group?

Doraiswamy: Mild cognitive impairment refers to people with memory problems that fall in the bottom fifteenth percentile of their age group. If you take everybody who's age 65 to 85 and you score them on a memory test, the people who score in the bottom fifteenth percentile, what we scientifically call as one standard deviation, is what we call as mild cognitive impairment. There's a few other research criteria for it. This is a very large group of individuals who have worse memory than average. They're concerned about it. Their memory may be slowly declining over time, but they're still independent and functional. This group is at very high risk for developing dementia due to Alzheimer's and other conditions in the short term. That's why we focused on this group because we felt this is the group for which we need to develop a preventive intervention and a lifestyle intervention would be very suitable for this group. Worldwide, my prediction is there's something like 25 to 30 million people with mild cognitive impairment.

Chin: So it's a large group and potentially a very motivated group wanting to do everything they can to prevent the progression to dementia.

Doraiswamy: 100 percent.

Chin: You mentioned this earlier when you talked about the advantages of computerized games and computerized testing, that there's a lot of data that you can collect, which I imagine is quite overwhelming for the study itself. How did you evaluate participants throughout the study? What did you actually do to know, one, that they were doing the tests and, two, that they were either getting better, not getting better or getting worse?

Doraiswamy: The holy grail in the field of dementia prevention is for a treatment to hit on three different goalposts. The first is you want to improve cognition, which is they're coming in with memory problems. You want to improve their memory, and you want to improve it noticeably by a clinically meaningful amount. The second is you want a treatment that not only just improves cognition in the lab setting, in the clinic setting, but that transfers to your everyday life. That's called functional improvement in your activities of daily living. The third metric of improvement is direct improvement in slowing the rate of shrinkage of the brain. One of the hallmarks of mild cognitive impairment and dementia is that there is progressive loss of brain tissue and the gray matter of the brain. The gray matter is where we house a lot of the cells that do the thinking for us. We wanted to see if this training can also slow the loss of that gray matter tissue through the use of MRI scans to measure the volumes of the cortex in the brain and the volume of the hippocampus, the memory center in the brain.

Chin: So given that, what did your study end up finding?

Doraiswamy: Very interestingly, it was a 78-week study. We randomized or enrolled 107 people with mild cognitive impairment that were assigned to either computerized games played on a computerized machine. The games were provided by a company called Lumos Labs that had developed a suite of games. The other half were randomized to crossword puzzles. Going in, we actually thought the new sort of computerized cross-training of the brain that is highly targeted, that's scalable, that's personalized to each individual skill level, would actually come out on top, but we were surprised. Our findings were the exact opposite of what we had predicted. Crossword puzzles did better than the computerized games. People in the computerized games condition tended to decline a little bit marginally. People in the crossword puzzles improved in their cognition, improved in their daily functioning and also had much less atrophy or shrinkage of the brain tissue over the 78 weeks of the study.

Chin: Did you notice a difference in these results between men and women or based on their genetic risk factors or genetic type? I mean, did you notice that there was a discrepancy in any of the subgroups?

Doraiswamy: There was no difference between men and women or based on the APOE genotype. What we did find was the severity of your mild cognitive impairment did influence your outcome. If you were very early in the disease process then both computerized games and crossword puzzles benefited you equally. If you were late in the mild cognitive impairment process then you tended to do better on crossword puzzles than on games. Now one hypothesis is maybe people who are late in the MCI process were struggling to play the computerized games. Maybe they were a little bit more sophisticated for them. The crossword puzzles were easier, more familiar, but we don't yet know definitely that that's the case but that's our presumptive explanation for what we found. We also looked at differences between caucasians and African Americans. African Americans did as well if not better than caucasians.

Chin: So this is an intervention that really benefits everybody, that has a pretty profound impact and you're seeing it across the board in the things that you were your metrics of studying this.

Doraiswamy: Absolutely, pennies on the dollar compared to some of the other treatments that are 25, 30, 40 thousand dollars.

Chin: You mentioned a hypothesis about potentially one thing that could be going on, but what do you think or can you speculate as to other potential underlying mechanisms? Like how is it that crossword puzzles can be therapeutic for brain disease?

Doraiswamy: We don't understand the mechanisms because one would then need to do a different kind of study to look at neural circuits underlying this. We don't really know the full mechanisms, but I think it's a classic complex mental activity that draws on many different functions in the brain and maybe that's what we need. It also engages people well. It's familiar. It draws on large language areas, it draws on reasoning. It's also fun. Maybe that's what it is. We don't understand fully the mechanisms, but it kind of goes back to that old ‘use it or lose it.’ That theory, maybe that's what crossword puzzles are drawing on.

Chin: When you think about the crossword puzzles and even just the other cognitive computerized games, do you think ultimately that the game matters or that there's a certain duration in which a person should be engaging in it, or if daily is better than three times a week? If you had to speculate just based on your research, based on your literature review, how do these variables come together?

Doraiswamy: I think one needs to have intense training for between eight to twelve weeks at least four days a week, and then one needs to have booster sessions to keep the intensity going. One does not necessarily need to do four days a week for like several years because nobody's going to do that and everyone's going to get bored and give up unless we can make the game really, really interesting like a social media engagement where you're competing against other peers and so on and so forth. My prediction right now is intense training for twelve weeks causes the hard wiring and the soft wiring of the brain to re-mold itself because neuroplasticity builds a habit and then you sustain that habit through booster sessions. Now we don't know this for sure, so we're actually designing a bigger trial that the NIH is – we've gotten a good score, we haven't gotten official funding. We want to test some of those other questions, like what is the optimal dose of crossword puzzles?

Chin: It seems to me – and I'm glad you explained it this way – an intensive first session that could be anywhere from eight to twelve weeks and then as you call the booster sessions later on just to sort of keep those neural networks firing and active. Do you have a sense, for people who are listening, how long each session in general could be or should be? We're not going to hold you to it. I'm just wondering for my clinic patients and for people who want to engage in crossword puzzles, or other games for that matter, how long is the appropriate amount?

Doraiswamy: Minimum half an hour, one hour if possible. Think of it as like a deep, deep engagement that you're doing. Many of us when we go to the gym we think about one hour as our minimum dose. When we go on a treadmill, we think about 45 minutes to one hour as a minimum dose. I think this can be thought of in much the same way. If you're curling up and reading a book, you have deep engagement for an hour. That's the kind of deep engagement that really, I think, induces neuroplasticity in the brain, because shallow engagement does not induce it.

Chin: That's really helpful. I incorporate your study into my own memory clinic practice and I'm going to have to make some adjustments because I appreciate the specific duration. It's a lot more than I was anticipating, I must say, but it also makes a lot of sense to me. People truly have to be engaged in order to create these new neural pathways.

Doraiswamy: Thank you for incorporating it. I think it's a fun study, and hopefully it'll be a scalable intervention worldwide.

Chin: I will tell you from personal experience with my clinic patients, people are motivated. If you give them the specific instructions and directions, like you're doing on this show right now, people are willing to try it and see. Oftentimes if it's fun, like you said, people are willing to incorporate it in their day. That actually leads to my next question though is, what about cross-training your brain? You bring up exercise and the different things we can do for exercise. Is there any idea – or maybe this is a future study that you're already planning – of different activities with crossword puzzles to increase effectiveness? I say this because many people like to play card games, or they do jigsaw puzzles, or the very popular Wordle or sudoku. I mean where do those things come into play?

Doraiswamy: I think cross-training – not just combining different complex mental activities but also combining complex mental activities with other lifestyle strategies, whether it be exercise or dietary interventions – I think that is likely to be much more effective than any one intervention by itself. A multimodal lifestyle intervention is really where we should go and we need to recommend and prescribe to patients a multimodal lifestyle intervention. Something very simple is – I've sort of coined a word for it – it's called curiosity walks. Walking is a great exercise. Walking at the speed at which you can talk is an even better exercise. Then walking with someone is great because you have social connectedness. Then walking with someone that you can deeply discuss a book, is to me, all of a sudden you're combining lots of different interesting activities into one single sort of easy lifestyle intervention.

Chin: That's one multimodal intervention right there, walking with someone and having a deep conversation. Possibly talking about your last crossword puzzle or the challenges in some of your games.

Doraiswamy: Exactly.

Chin: Now this was a computerized crossword puzzle, so my next question really is do you feel like paper crossword puzzles is acceptable? If not, or even if so, do you have certain websites or applications that you think of are potentially helpful? I know it's not an endorsement for any particular company or not. When your patients or research participants ask you, “Well what else can I do?”, what do you usually tell them?

Doraiswamy: Yes, I think paper crosswords will work just as well. Some people like to play it on their Kindle. Some people like to play it on their mobile phone. Some people like to just sit, as you said, –on their patio drinking a cup of coffee and playing it. Whatever is the best suited for your lifestyle, that's what you should pick because you want to pick what you can stick with. If a paper sudoku or a paper Wordle is what works for you, by all means do it. If a crossword puzzle book is what you like, by all means do it. If you like playing bridge or if you like playing chess then that's also probably equally a complex mental activity. The key thing is the idle brain, while it's good for some other things like coming up with creativity and new ideas and stuff, I think try to involve yourself in some complex challenging mental activity and grow over time. Watch your scores and track it and become better and better, like become really good at the Monday New York Times crossword puzzle, which is the easiest. Then see if you can graduate to the Thursday, which is the medium challenging, and then graduate to the weekend puzzle, which is the toughest. Your brain likes that challenging aspect of it and it also likes novelty so mix things around.

Chin: I think back to our comments about the amount of data that you're collecting and the different use of these technological tools. What do you think the future role of technology is, in particular artificial intelligence, when it comes to someone's cognitive health and cognitive training?

Doraiswamy: I think technology is going to play a huge role in multiple different ways. We have already shown that you can use AI to detect risk for Alzheimer's disease five or six or seven years before someone actually develops memory problems simply by scanning through the electronic health records and putting together some risk factors. We have also worked with a company called Lumos Labs to create what I think will become the future of brain health, which is we cannot anymore just study like a hundred people in two sites or like even 1,000 people at five or six sites. We cannot just study white brains. What we need is a crowdsourced global brain lab and Lumos Labs in California has created something like that. They've created a global neural lab of 40 million people from 180 countries who are voluntarily contributing health data as well as cognitive testing and memory data, as well as lifestyle data. You have now 100,000 people in each age group who are contributing data. You have people contributing data on sleep, on exercise and diet and you can start to draw some very, very interesting correlations. That, to me, is the future. We will have a real-time brain platform on our smartphone that tells us what we need to do and access a sort of personal avatar, if you will a personal brain coach. That's sort of the future.

Chin: Yeah, I look forward to that day. Although, I'm not sure I want to be nudged so often that I need to get up and do something and engage in a cognitive game.

Doraiswamy: Well, you can turn it off if you don't want it, right? You can always turn off notifications on your Instagram, but nobody does because they love it. [Laughs]

Chin: You hinted to this, but now I'm going to be very direct and this is going to be my last question for you. What do you do personally to keep your brain as healthy as possible?

Doraiswamy: I do a lot of things. I mean, luckily I'm in academia so complex mental activity is what we have to do to survive here in the publish or perish world. There's something we haven't talked about which is the reverse. I think sleep to me is the single most important thing that all of us can do for brain health because sleep six to seven hours a day is essential for archiving our memories, for our brain health and possibly even for getting rid of some toxic metabolites that accumulate during all the daytime metabolic processes. That's one. Two, I'm mostly a vegetarian. A Mediterranean diet is – what at least we believe – is one of the most brain healthy diets, but Indian diets are also relatively healthy. There is some evidence that turmeric, one of the ingredients in curry, may be protective for the brain. It's not definitive. I exercise, I play tennis. I challenge myself a lot and I surround myself and talk to one interesting person every day.

Chin: That's a wonderful way of phrasing it, one interesting person a day. That's a whole group of activities and I'm sure keeps you very busy, Dr. Doraiswamy, so I appreciate you coming on the Dementia Matters podcast. We certainly look forward to having you on once you have more data.

Doraiswamy: Thank you so much. It's been an honor to be on your show.

Outro: Thank you for listening to Dementia Matters. Follow us on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts or wherever you listen or tell your smart speaker to play the Dementia Matters podcast. Please rate us on your favorite podcast app – it helps other people find our show and lets us know how we are doing. Dementia Matters is brought to you by the Wisconsin Alzheimer's Disease Research Center at the University of Wisconsin--Madison. It receives funding from private, university, state, and national sources, including a grant from the National Institutes on Aging for Alzheimer's Disease Research. This episode of Dementia Matters was produced by Amy Lambright Murphy and Caoilfhinn Rauwerdink and edited by Taylor Eberhardt. Our musical jingle is "Cases to Rest" by Blue Dot Sessions. To learn more about the Wisconsin Alzheimer's Disease Research Center, check out our website at adrc.wisc.edu, and follow us on Facebook and Twitter. If you have any questions or comments, email us at dementiamatters@medicine.wisc.edu. Thanks for listening.