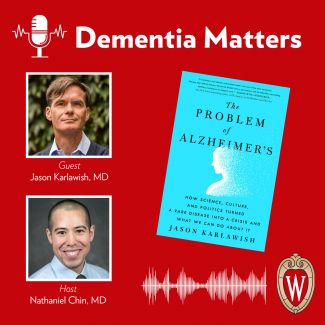

Dr. Jason Karlawish joins the podcast for the third installment in our series on his new book, "The Problem of Alzheimer's: How Science, Culture, and Politics Turned a Rare Disease Into a Crisis and What We Can Do About It". In this episode, Dr. Karlawish discusses the healthcare system’s role in Alzheimer’s disease and what it needs to do better to care for individuals with dementia and help them live well. Guest: Jason Karlawish, MD, co-director, Penn Memory Center

Episode Topics:

- What did you learn about the healthcare system in your work with Beverly and Darren Johnson? 1:33

- What do we need in healthcare to better care for individuals with cognitive impairment? 3:25

- Do we need more memory care specialists in the field, or can primary care physicians do this work? 5:32

- How do we encourage more individuals into enter the geriatric care medical field? 7:38

- How do we increase the number of memory centers and how should they function within our current healthcare system? 9:22

- Why is it important to discuss delirium? 11:14

- What does a multidisciplinary team offer in dementia care? 13:03

- What services and supports do you envision for the healthcare system? 14:57

- The importance of being respectful in communication and interaction with older adults. 18:06

- What did you learn from working with Dr. Jeffrey Kaye from the Oregon Center for Aging and Technology (ORCATECH)? 20:34

- What role does our government have in addressing this humanitarian crisis? 23:13

Learn more about Jason Karlawish's book

Find Dementia Matters online

Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

Subscribe to this podcast through Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Podbean, or Stitcher, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Show Notes

Dr. Karlawish's new book is The Problem of Alzheimer's: How Science, Culture, and Politics Turned a Rare Disease into a Crisis and What We Can Do About It. Learn more at his website.

Dr. Karlawish is co-director of the Penn Memory Center.

This is part three in a four-part series. Listen to Part 1, "The Past, Present and Future of Alzheimer's Disease Research." Listen to Part 2, "How Culture, Society and Politics Shaped Alzheimer's Disease Research."

Transcript

Intro: I'm Dr. Nathaniel Chin, and you’re listening to Dementia Matters, a podcast about Alzheimer's disease. Dementia Matters is a production of the Wisconsin Alzheimer's Disease Research Center. Our goal is to educate listeners on the latest news in Alzheimer's disease research and caregiver strategies. Thanks for joining us.

Dr. Nathaniel Chin: Welcome back to Dementia Matters. I'm here with our guest Dr. Jason Karlawish for our third installment on The Problem of Alzheimer's Disease. It's still a problem, Jason, and we have not solved it though. You've nicely described its origins in your book.

Dr. Jason Karlawish: Yeah, another problem.

Chin: I'm not going to do your bio again, so instead I'll share some fun facts that you haven't mentioned in any of your prior interviews or essays. Two of them; you are a dedicated distance swimmer with hopeful plans of swimming in our own lakes here in Madison, Wisconsin, Lake Monona in particular, and you raise whippets. I guess my first question is, what got you into raising whippets? (laughs)

Karlawish: (laughs) When I met my husband, John, he had a whippet named Zoe. I suddenly got to discover this most charming breed of dog. After that it was Juno and then Daisy and Sonny – not named simultaneously. That's the way it worked out, so currently we have Daisy. Yeah, so it's our fourth whippet.

Chin: (laughs) That's wonderful. In our prior two episodes, we covered the history of Alzheimer's disease, the science, as well as the culture, society, and political influences on it. Today we're going to discuss our healthcare system's role in Alzheimer's disease, or as you call it in your book, “The House of Alzheimer's.”

Karlawish: Yeah.

Chin: You depict a part of our healthcare system in telling a story of two of your patients, Beverly and Darren Johnson. In that story, you ask them a profound question – why should life be any different now? I'd like to start by asking you, what did they say to you when you asked them that and what did they teach you in your time with them?

Karlawish: Life for them was different because they had encountered such poor care in the healthcare system up to that, namely the hunt for a diagnosis and also the stigmas that surrounded the disease. Namely, we're not just going to talk about it. The challenge that we've faced – the memory center – is helping people to overcome those stigmas, be able to talk about the problems, make sense of them, and then provide them the education and training that they need to put together a day that's safe, social, and engaged. In some sense I've come to see this as kind of like acknowledging their disabilities and what are the reasonable accommodations that are going to be needed to address those disabilities. Of course – I think as you and I both know, given our clinical practices – we have a health care system that's not really set up to provide those reasonable accommodations so that people can live well despite of and with a diagnosis of dementia caused by Alzheimer's or whatever other disease may be the cause.

Chin: Well, that's a nice transition to, what do we need in healthcare to better care for the people with Alzheimer's disease or any cause of cognitive impairment?

Karlawish: Yeah, and there the geriatrician in me really came out in that part 3 of the book, “Living Well in the House of Alzheimer's.” You know, I called it “the house of Alzheimer's,” which actually for a while was going to be the title of the whole book and it was a good working title; I've really come to appreciate working titles. The geriatrician, though, in me came out. There are things we can do right now, and in some places we're doing them. Slowly Medicare, in particular, is coming around to making them the norm rather than the exception but I mean I start out in the book with just a basic thing, which is setting up a clinical infrastructure so people can get diagnosis and access to care. You and I both are part of memory centers that are made possible because of large grants, frankly, as well as some philanthropy and cross subsidies. That's just not a sustained business model. You know, I could only find one memory center out in the community that is not a clinical trial shop. I profile the work of Dr. Peggy Noel in her memory center in Asheville, North Carolina, but we need to create a financial model that allows memory centers, dementia centers, to exist. That's just the start, you know. I talk in the book, how access to core long-term care services and supports needs to be made possible. Namely, there just aren't enough adult day-activity programs out there because, again, the money isn't there to sustain them and so they struggle. Then I go to the hospital. You know, I like to say that delirium is to Alzheimer's as pain as to cancer. We need to think about restructuring the way we run hospitals to implement the proven techniques from the HELP program that Sharon Inouye developed. I profile her story that can reduce the risks of developing delirium. You know, there's more there we could talk about – the hip fracture work and whatnot. You want to go there too?

Chin: I actually – I do want to get into delirium but let me stop and just ask this too though. As you talk about memory centers and care needed, do we need specialists to treat and address Alzheimer's disease or can this be done in a primary care oriented environment?

Karlawish: I think it's both. I think, much like cardiovascular disease, there certainly is a vast number of patients for whom the general intern, with enough resources, can do the work that needs to be done to provide the care, but just like with cardiovascular disease – and I remember back when I used to do general geriatrics, I had patients who I would refer to cardiology because things just weren't going the direction I thought they should go in. I think that the problem right now that general internists face, certainly for some it's a question of the skills but even for those who have the skills, there's just some fundamental resources that are almost kind of comic that they need. I say comic because they're so basic like an exam room that has enough chairs, a few extra minutes in a visit so that they can actually talk to the family member and get history, which of course means reimbursement that's appropriate because you're taking more time. There's some things as I look back I wish I had in the book. I mean, I spent a fair amount of time, unfortunately via phone, talking with folks in the Netherlands – I wasn't able to make the trip there – and learned all about how there that's the system they have. It's expected that the primary care physician is adequately resourced to work up a cognitive complaint, adequately resourced meaning they can divide up the assessment over a few visits so they can take the time that's needed and they know when to refer, and that referral network is available to attend a special clinic for – you and I both know the kind of cases we're talking about – language presentations, visual-spatial presentations of the disease that are just harder to work up until you have a real comfort with the sort of cognitive neurology aspect of it.

Chin: And then flipping to the specialist part, so geriatricians, neurologists, geriatric psychiatrists, there's not a lot in each of these fields that specialize within memory. Frankly for geriatrics, like you and I, this is not a very popular field. Where do we get this workforce to help provide care for people with cognitive change?

Karlawish: Yeah, we have a problem. I mean, the average neurologist does not graduate from a residency program skilled in diagnosis and treatment of persons with living with dementia. To a psychiatrist and frankly, I think as a geriatrician, I will say, we're good with some aspects of dementia care and diagnosis but we have wide gaps so there really is going to need to be a crash course, I think, in learning here for the professions. You know, I'm afraid that we're to blame for that. I mean, doctors are economic actors and incentive systems since Medicare’s founding in ‘65 were not aligned to promote clinical practice, particularly in the outpatient setting that addressed the problems of aging adults, particularly the problem of dementia, the problem of Alzheimer's. I think if there's one outcome of this miserable pandemic it’s that we have learned now about telemedicine and its possibilities as well as tele-education. I mean, I can't wait to get back in-person, live with colleagues to learn, but I also have learned the value of remote techniques for lectures and things. I have a cautious optimism that we may begin to create hub and spoke models for telemedicine and tele-education to begin to sort of jigger the workforce so that they can provide the care that's desperately needed.

Chin: I appreciate that cautious optimism. Now going back to the memory centers because I think that's such a huge piece of this; how do we get more memory centers in our healthcare system, and then how do these centers function within the current system that we have of healthcare?

Karlawish: Well, we're going to have to spend some money to save some money. I mean, I just think that one cautiously optimistic event that's occurring on the national level is the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, CMMS, has created what's known as Comprehensive Primary Care, which is otherwise known as CPC. It's still a demonstration project but you can clearly see that they want to encourage healthcare systems and that the emphasis there is on systems to identify persons with Alzheimer's disease and related disorder diagnoses and provide the kind of comprehensive care they need with, for example, the introduction of things like care managers, mental health services, et cetera. When I look at the CPC program, you know – literally go to the website – it's meritorious. It's got the right intention. The question is, of course, getting it out there and making it work economically. I will tell you; I've had chats with folks who run or otherwise are senior leaders in healthcare systems and there's a little fear about this kind of approach because it all does truly come down to money. I mean, you know, knee replacements still are the golden ticket for a healthcare system to make money. It just makes no sense if you look at the events of COVID. The hospitals were packed – packed – with patients, and yet they lost money. There's something wrong there. There's just something wrong that you've got a system set up that even though your hospital was filled to the roof you lost. It shows you the craziness of the incentive systems we've created.

Chin: And then speaking of hospitals being full, delirium happens quite frequently in a hospital. You do spend quite a bit of time in your book talking about delirium and capacity, both really key components. Share with our audience why that matters in a book about Alzheimer's disease.

Karlawish: Well, I like to say that, you know, delirium is to Alzheimer's as pain is to cancer. Not all people with pain have cancer, but boy if there's one symptom, one complication of cancer that we all know about, it's pain. Indeed, this country engaged in an almost bizarre “let's make pain the fifth vital sign” and the rest is the history of the opioid epidemic. In contrast, certainly patients, persons developed delirium – acute confusional episodes either characterized by lethargy or agitation – from a variety of different insults to their brain. Many – some don't have any cognitive problems, but I think you and I both know – and the literature amply documents – that having cognitive impairment, having dementia, is a big risk factor for developing delirium because you're admitted for a heart attack, a urinary tract infection, a fall with a fracture, whatever. I went to the source. I interviewed Sharon Inouye and learned her story of becoming one of the first scientists dedicated to studying delirium. She really worked out what was otherwise considered just “this is just what happens to older adults.” Much like senility, you know, it's just what happens. She said no, this doesn't have to be that way. Her work was very clever. She identified the risk factors and, most importantly, she showed if you manipulate those risk factors you could reduce the risk of getting delirium. She turned something that just was like the winter – there's nothing you can do about it – into something that is tractable. In that sense, I think she's one of the heroes of the book.

Chin: And in your book, you often mention the importance of team. You have a team in your memory clinic. I have a team. What does a multidisciplinary team offer, and why does it matter in aging and particularly in dementia?

Karlawish: Yeah. You know, I had a revelation when I wrote that part of the book. It's a chapter called, “Discernment,” and I picked that title, “Discernment” – it's actually, I’ll get to that in a minute – because I realized that a lot of these innovations were about creating multidisciplinary teams. Of course, we say that, we all nod. It's sort of a virtue kind of rhetoric, you know – who doesn't want a multidisciplinary team? It sounds so good, but what's going on there is a change of culture. That's what I think we're talking about when we're talking about multidisciplinary teams. We're saying that the ways that we have organized care, the ways we think about providing care are wrong. We have to arrive at a recognition that we need to work with other people in different ways. Okay? That's the process of discernment, and that word actually comes from a Jesuit tradition of, sort of, a perfecting of one's character and soul to recognize one's faults in a kind of endless process of sort of recognition and correction. It's a process within the Jesuit nomisary area of discernment. That's what I think the healthcare systems need to do. I mean, they were working in teams when they were taking care of my grandfather – who they actually killed after his hip fracture but it was a crazy team. It was a team that was well-aligned to make sure he had the best surgery and, you know, his hip was repaired and it worked well – anesthesia, surgery, you know. It was a team, but it wasn't the right team. That's this culture change that needs to occur – different teams thinking differently. That's this process of discernment.

Chin: Very powerful word. I didn't appreciate it when I read it in your book; I appreciate it now. You talked earlier about the activity center and in your book you talk about adult activity centers or daycare centers – whatever terms you want to use. You illustrate the power of such things and I really like your example of a bean bag toss.

Karlawish: Yeah.

Chin: Can you comment for our listeners, what services, supports – non-medication related – do you envision for a better care system?

Karlawish: Well, several but one that I foreground in the book is adult day activity programs. You're right, also sometimes called adult daycare – a term that I think just doesn't work on a number of levels. It is about activity, and so that probably is the better term for it. I visited one of them. I visited Mainline Adult Day Program in Mainline, Philadelphia and Pat, who ran it, took me on a tour. It was so impressive to meet her and her dedicated staff creating a space that was safe, social, and engaged for individuals with cognitive impairment. One of the revelatory moments when I was there was when she talked about how, you know, many families typically come too late. They've been reluctant to participate and often when they come there, some things that – one thing that many of them say, in the sort of a rueful kind of dark humor, is, “You know, I don't want my dad playing bean bag toss,” or they just comment on that. She says, it's so ironic because if there's one activity which we find really brings out the residents’ enjoyment and engagement, it's bean bag toss because it's a team activity. There's some degree of competition. It's cognitively engaging; you’ve got to keep track of the score, who's winning. It's physically engaging; standing, tossing, etc. She just – I was so moved by that that I put it in the book, which is the need to kind of – you have to just see this world differently and get over the stigmas as well. I mean, I understand the stigma of a son dropping off his father who, once upon a time, was a leading professor in the university and now is enjoying playing bean bag toss. I mean, I understand the mourning that that family member experiences and yet, his father enjoys that activity. You know, that Mainline Adult Day Care shut down. It shut down because COVID, obviously, kept people away and they simply didn't have the resources. It's so sad, you know, to just sort of sustain things as they managed. They weren't part of a healthcare system, as most of them are; that is the case. So, you know they had a limited endowment, limited reserve and maybe they'll get back going again now that we're back together again, slowly in the region here. I just thought that was such a sad thing. It's not in the book. Obviously it's just a sad day, that these activity programs are out there in the community struggling to basically make salary and sustain themselves, and yet they provide such good.

Chin: You know, your response makes me think of when I am with fellows and residents and med students. I always want to train them to be respectful of people with dementia. They're human beings, respect their autonomy, their individuality, and don't treat them like a baby. That's a really important thing, and you mentioned that in your book about the language that we use. Sometimes I fear we swing too far and we just assume that older people can't have fun or play games. I experience that in clinic when I talk about adult coloring and the value of potentially coloring pictures and how that can be actually mindful and stimulating and yet calming. It seems like we just have to find this balance between being respectful, not babying people, but at the same time allowing them to toss a bean bag and have fun.

Karlawish: Yeah, but I do think it does come down to being respectful through communication. I actually have a whole chapter, “Not Legally Dead Yet.” It's about capacity assessment, but it's really about communication. I will say, I don't do hospital-based care anymore, but when I did I would spend some time with the residents really having them scrutinize the way that they spoke with the older adults. I once had a very vigorous exchange with a resident who felt, ‘Well, they're so scared and if we talk to them like with the – (change tone to be slower and enthusiastic) talk to them like this so that they don't feel so scared, (regular tone) that that's a good thing. I said, “Well, I acknowledge there you may walk into a room and have a social connection, an emotional connection, with someone where you realize they're panicked and you need to use a soothing tone of voice, but the default ought to be you talk to adults like adults at a tone of voice like I'm talking to you right now.” Phrases like, ‘he's so cute,’ to describe an older adult, I just think that is so inappropriate. I don't know, I think start with the default of you talk to adults like adults. If you develop a relationship such that calling them cute and whatnot seems to be where you're going to go with it, so be it, but to make the default a sing-song, baby talk, high-pitched, ‘you're so cute,’ I just find that – the beginning of it, it's an othering. What it usually reflects is the discomfort of the interlocutor with the other person. Yeah, I think that's incredibly important for dignity and quality communication.

Chin: Also in your book then you do meet this very innovative physician, Dr. Jeff Kaye. You write about the use of technology and he's monitoring people. He's helping people.

Karlawish: Yeah, yeah.

Chin: It was something. What did you learn from that experience and do you think that method is practical?

Karlawish: Yeah, so Jeff Kaye at Oregon Health Sciences University has what's called ORCA tech. Jeff’s a neurologist who was doing standard biomarker type research, et cetera. He went to this conference somewhere in the Pacific Northwest where Intel and other tech folks were there and he suddenly had this revelation like – why aren't we using this technology to gather the data that we otherwise spend our time in these incredibly artificial interviews with informants asking them to recall things that are full of biases, et cetera? Why don't we just – function is the problem. Let's measure function. The rest is history. He has set up this living laboratory and I visited some of the apartments right next to OHSU – Oregon Health Sciences University – that are all wired up if you will, where you can detect motion through the room, time spent on the bed, use of the medication box, refrigerator opening time, driving habits in terms of frequency out on the road, et cetera. I mean it really is quite – computer use! You know, time spent on the computer. I bring that one up because he has a great paper that shows a predictor of developing mild cognitive impairment is decline in the amount of time people spend on the computer. The point is that there's so much of our lives, courtesy of the internet of things, that can be monitored to both detect and then monitor cognitive impairment, and he's doing it. The challenge, of course, is in interconnecting these various, different kinds of light bulbs and whatnot and a system that will work. Then, of course, there's fabulous challenges related to how we're going to use this information in our clinical practice. I talk about how it upends the way we communicate because now you come to me and I ask you questions to find out what's going on. In a future world, I get a report about how you've been doing and I have to figure out how to engage you in a discussion of what I've observed about your driving habits and whatnot, but I mean let's rise to that challenge and face it. Yeah, I have great hope that technology can be a way to allow us to live independently. Of course we're going to have to surrender some privacy to achieve that.

Chin: To end this episode, I'd like to talk about what you call, “Hope in a Plan.” As I read this section, this showed me the power, the influence of political and social organizations putting needed pressure on our government to act. What role does our government have in addressing this humanitarian crisis and what steps have they made so far?

Karlawish: “Hope in a Plan” was one of the most fun chapters to write, also to research. It's a great story of politics, in the grandest sense of politics. Namely activists – non-scientists – realized we're not making progress against this disease. We simply are not putting enough money into the research and we're tinkering with our healthcare system, throwing a little bit of money, creating programs that then disappear, et cetera, and we really need to take this problem on. What the activists realized though was that the approaches that they were taking just weren't working. We're talking around about like 2005 here up to about 2011 when things break with the signage of the National Alzheimer's Project Act by President Obama. What I chronicle in “Hope in a Plan” is the work of two individuals who led organizations. One is George Vradenburg who runs an organization called UsAgainstAlzheimer's and the other is Harry Johns, who was and is the president and CEO of the Alzheimer's Association. I chronicle, I think in kind of meticulous detail having interviewed both as well as others around them, how they went about working with congress to try and change funding. What's interesting, without spoiling the story, is they ultimately went about it in two very different ways. Harry Johns emerges really as kind of the hero of the story, if you will, because he decided along with Bob Egge – excuse me, Robert Egge – of the Association's lobbying group, the AIM – Alzheimer's Impact Movement – to adopt a very different strategy. They were brilliant, I mean. It led to the passage of the National Alzheimer's Project Act and therefore an enormous increase in federal funding for research which remains today, as well as the beginning of a reorientation of the federal government about how they approach Alzheimer's disease. I think the latter is an unfinished project, which I think remains. We'll see. I think the next key event in our history is going to be what happens in the midterms and the balance within the house and senate in order to move legislation forward. That's going to make a difference here.

Chin: Well, thank you for your insights, Jason. I'm hopeful more change is coming and books like yours are going to lead to these changes through active discussion. We have one more discussion left and I think it'll be the most interesting. I'm going to ask Dr. Karlawish to lay out what he thinks society can do to help this humanitarian problem that we call Alzheimer's disease, so we're going to delve into wealthcare, creative strategies to care for others, and the important issue of stigma. Tune in to hear more.

Outro: Dementia Matters is brought to you by the Wisconsin Alzheimer's Disease Research Center. The Wisconsin Alzheimer's Disease Research Center combines academic, clinical, and research expertise from the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health and the Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center of the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital in Madison, Wisconsin. It receives funding from private university, state, and national sources, including a grant from the National Institutes of Health for Alzheimer's Disease Centers. This episode was produced by Rebecca Wasieleski and edited by Bashir Aden. Our musical jingle is "Cases to Rest" by Blue Dot Sessions. Check out our website at adrc.wisc.edu. You can also follow us on Twitter and Facebook. If you have any questions or comments email us at dementiamatters@medicine.wisc.edu. Thanks for listening.